Imagine the limited aspirations of the first

pre-bronze age constructor to join two pieces of wood with a sharp implement.

History does not record who it was, but the incredible results

of that inspirational moment are all around us - in the houses we live in, the bridges we

cross, the furniture we sit on.

Nails have been around for a long time. As soon as man

discovered that heating iron ore could form metal, the ideas for shaping it quickly

followed.

Wrought handmade nails (Wrought =

beaten into shape by hammer blows)

In the UK, early evidence of large scale nail making comes from

Roman times 2000 years ago. Any sizeable Roman fortress would have its 'fabrica'

or workshop where the blacksmiths would fashion the metal items needed by the army. They

left behind 7 tons of nails at the fortress of Inchtuthil in Perthshire.

For nail making, iron ore was heated with carbon to form a dense

spongy mass of metal which was then fashioned into the shape of square rods and left to

cool. The metal produced was wrought iron. After re-heating the rod in a forge, the

blacksmith would cut off a nail length and hammer all four sides of the softened end to

form a point. Then the nail maker would insert the hot nail into a hole in a nail header

or anvil and with four glancing blows of the hammer would form the rosehead (a shallow

pyramid shape).

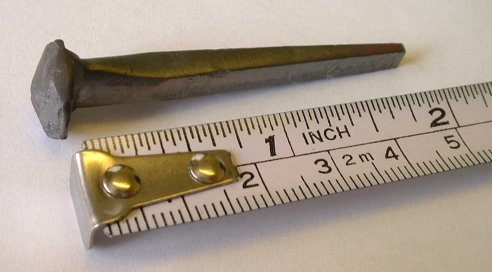

An original 7" (180mm) long Roman nail found in Scotland

This shape of nail had the benefit of four sharp edges on the

shank which cut deep into timber and the tapered shank provided friction down its full

length. The wood fibres would often swell if damp and bind round the nail making an

extremely strong fixing.

In Tudor times, we have evidence that the nail shape had not

changed at all as can be seen by the nails found preserved in a barrel of tar on board the

'Mary Rose' - the Tudor flag ship of Henry VIII built in 1509 and recovered from the mud

of the Solent in 1982.

A replica of the hand made nails found on board the 'Mary Rose'

Machine made nails

It was not until around 1600 that the first machine for

making nails appeared, but that tended really to automate much of the blacksmith's job.

The 'Oliver' - a kind of work-bench, equipped with a pair of treadle operated hammers -

provided a mechanism for beating the metal into various shapes but the nails were still

made one at a time.

Eventually, in the USA, towards the late 1700's and early

1800's, a nail machine was devised which helped to automate the process. This machine had

essentially three parts. Flat metal strips of around two feet (600mm) in length and the

width slightly larger than the nail length was presented to the machine. The first lever

cut a triangular strip of metal giving the desired width of the nail, the second lever

held the nail in place while the third lever formed the head. The strip of metal was then

turned through 180° to cut the next equal and opposite nail shape off the strip. These

nails are known as cut nails.

Because the nail up until then was handmade, the first machines

were naturally designed to re-produce the same shape of product - a square tapered nail

with a rosehead, but only tapered down two sides of the shank.

Soon nail making really took off, primarily in the USA and also

the UK with its captive markets of the British Empire. The cut nail was produced in large

numbers and various other shapes were devised to suit different purposes.

In the heartlands of the industrial revolution, many nail

factories had row upon row of these nail machines and the incessant clatter from them

created a deafening sound.

This old photograph from the early 1900's shows a typical nail shop -

notice the machines are pulley driven

But still, the process was labour intensive with a man (or

woman) attending each machine.

By the start of the 1900's, the first coils of steel round wire

were produced and quickly machines were designed to use this new raw material. The first

automatically produced wire nails with no human intervention other than to set up the

machine immediately showed that this was the way to produce a cheaper nail.

The fact that the nail had a round parallel shank that had up to

four times less holding power didn't matter so much. Thinner timbers were being used in

construction and other forms of fastening were becoming available if a strong fixing was

needed.

The wire nail quickly became the nail of choice as it is today

because of its price and the cut nail's day was numbered.

In the 21st century, the nail making process through the ages is

now being used by the restoration industry to help to establish when a building was built.

Hand made nails suggest the building was built before 1800. Cut nails suggest the building

was built between 1800 and the early 1900's. Wire nails will be found in a building put up

in the period from then to date.

Hand made nail (top) Cut nail (middle) Wire nail (bottom)

Restoration

There is currently an enormous interest in preserving our

heritage and much of that heritage is in the shape of the buildings that remain as

evidence of a bygone age.

For the restorer, it is vital that the correct raw materials are

used in any attempt to preserve an old building. Nails are no exception. The restorer is

looking to use similar nails to ensure the authenticity of the restored building.

While it is possible to get a blacksmith today to produce a

handmade nail from wrought iron, the cost can be prohibitive and the blacksmith is not

keen to devote his limited time to making such small products.

However, almost a century after their predicted demise, there

are still two cut nail manufacturers worldwide in existence employing the process that is

almost 200 years old and using machines that have barely changed in design in that time.

One such company is Glasgow Steel Nail Co which can trace its

business roots back to 1870. In addition to working with these old machines, the

process also involves preserving the blacksmith's skills to form cutting and heading

tools.

A new cutting tool is removed from the smiddy fire

As explained earlier, the first cut nail machines replicated the

handmade nail - the square tapered nail with a rosehead. Because the process still

involves a man (or woman) presenting a strip of metal to a machine, the resulting nail is

necessarily imprecise - that is each nail can look a little different to the next one.

A view of a cut nail machine today - notice the ear protection!

Click here to watch a movie

of the process

The result is that these cut nails are often mistaken for

handmade nails. In use, the rosehead is often the only part of the nail that is left

visible and this shape of head is now considered vital when a period nail is demanded.

A Décor nail used mainly for studding on doors

Whether the project involves restoration or the building of a

replica, a genuine cut nail made using a process that has not changed in 200 years lends a

degree of authenticity to the project.

The nails are normally made of mild steel and are often used

without any further finish and can be clinched (i.e. bent over by 90° to lock the nail in

place). A recent expensive project involved nails for studding on large outside doors

which would be deliberately left to rust to provide greater authenticity. Nails can also

be produced in copper and bronze.

Glasgow Steel Nail Co has been involved in many interesting projects that have included providing nails for the Globe Theatre

in London, restoration work on Stirling Castle and other castles. The nails are generally

used for doors, floors, gates, indeed anywhere a period nail has to be displayed. The

company is also prepared to consider special projects, for example, it produced a bronze

boat nail for the building of the replica ship the 'Matthew' that in the year 2000

re-traced the 500 year old voyage of John Cabot who discovered New Foundland.

The bronze nail specially made for the 'Matthew'

Traditional cut nails worth preserving?

Over the years, the cut nail has faced the problem of

competition with its rival the wire nail and its history as the first common nail.

One aspect of that has been the expectation that because wire

nails are cheap, the cut nail should also be cheap. After all, it's just a nail.

Attempting to follow that line of thought, no matter how ridiculous as the processes are

so different, has meant that many cut nail manufacturers have ceased business over the

years because margins were so low.

The process is as much part of our heritage as the products

produced and it will be necessary for those involved in the restoration industry to change

the mindset of trying to compare cut nail and wire nail prices, if the process is to

survive.

One way of changing the mindset is to think in terms of the

price per nail in comparison with other old artifacts being used and indeed what can be

purchased today. Cut nails for the restoration industry can amount to just a few pence

each and it only takes a moment to assess their long term value say in comparison with the

can of Coca Cola or Mars Bar you might buy for lunch.

A recognition of the value cut nails offer is needed to ensure

that the process is not lost for ever and encourage the handing on of the skills involved.

Indeed, the price is not dissimilar to that charged for hand wrought nails in medieval times.

You can read in more detail

about the early nail trade in the UK if you click here.

You can read another article

on the history of nail making if you click

here.

For even more detailed

information on nail chronology to help determine the age of a building; the shapes of hand

made nails; the first cut nails which were then headed in a second process; the fight

during the period 1790-1820 to be the first to design the best 'one process' cut nail

machine; or you would like to look at the British Army's Nail Standards manual dated 1813,

here are the sources for these articles particularly the ones noted below.

Lee H. Nelson: Nail

Chronology As An Aid to Dating Old Buildings, Technical Leaflet 48. Nashville: American Association for State and

Local History, 1968,

Maureen K. Phillips: Mechanic

Geniuses and Duckies, A Revision of New England's Cut Nail Chronology Before 1820,

APT Bulletin Vol. XXV No. 3-4, and Mechanic Geniuses and Duckies Redux: Nail Makers

and Their Machines, APT Bulletin XXVII No. 1-2. Association for Preservation Technology

International